Francis Bacon: Invisible Rooms, Tate Liverpool, until 18th September, £12 (including Maria Lassnig)

When I was in about year 8, I went on a school trip to Tate Britain. I remember walking past some paintings by Francis Bacon, and I didn’t like them. They were ‘weird’, I didn’t understand them, and at the time that fit in with my view of what art ‘was’. And with that, I didn’t give him much more thought. Which sounds bad but then again, I didn’t really pay much attention to any art until I fell in love with it at university. Even after 10 years, there’s a lot (and ever increasing) amount of art to look at.

So I was keen to go and see this new exhibition – the latest ‘big name’ at Tate Liverpool – to do a personal reappraisal of Francis Bacon. And whilst he didn’t suddenly become my new favourite artist, I feel like I ‘got’ something about him. I definitely realised why I didn’t like it back then, for the paintings in this show are dark – literally and thematically. And I hadn’t been a teenager for long enough to be hung up on emotional darkness yet. It wasn’t the paintings fault, it was me, I wasn’t ready for them. But now, with more ‘life’ under my belt, it all makes a lot more sense. Bacon wasn’t interested in the niceities of life, but he was excellent at painting the truth.

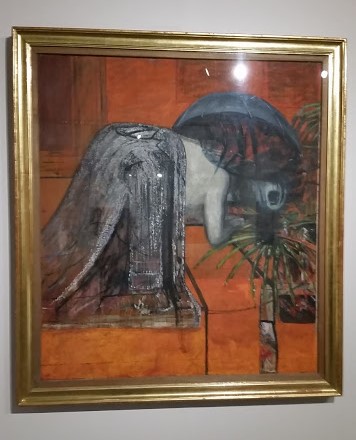

The Magdalene, 1945.

Take The Magdalene, made just after the war and generally considered to be a response to the events of that time. She’s a strange and disturbing figure – and for me, one of the most realistic depictions of mourning I have ever seen. Bacon understands what mourning feels like beneath all the formalities and expresses it in that blank, screaming face.

The show is called “Invisible Rooms” because of the way that Bacon sets many of his subjects in spaces to ‘trap’ the image, as a photograph does, but able to capture more. His work was, by his own admission, affected by his experience of living through a time of violence, and the emotions they express don’t get any more cheerful as the exhibition goes on. The ‘rooms’ made me feel, on more than one occasion, like I was seeing something I wasn’t meant to be seeing. Take Crouching Nude. Bacon wasn’t the first or last person to paint a nude subject, but few have seemed to be in such turmoil. The figure isn’t about desire, it seems bent over in despair. You feel like you’re spying on some private pain here. The other great example of spying on something (I thought) was Triptych, 1967, but I’ll leave you to discover that yourselves.

Crouching Nude, 1951

I was interested to learn that Bacon denied ever doing preliminary sketches for his paintings, but there’s a lot of them on display here. Why would he have done this? Maybe he thought that preparation takes something away from the immediacy of the emotion he wanted to be the focus, and instead makes you focus on the composition.

This exhibition, in a way, made me think of Instagram. Through it (and social media in general), we can control our self-image as much as we like, but we know that it is not capturing the truth of our selves. But a world where we only understand each other superficially would be a sad world to live in. Towards the end of the show they have 2 photographs taken of Francis Bacon’s studio in 1998, 6 years after his death. They are interesting as a document, but they feel cold and lifeless after the raw emotion of the paintings that surround it. This is why Bacon’s paintings, as brutal as they are, are necessary – they force you to look and feel more and consider their subjects in a way which is not always pretty but, on a human level, essential. I’m glad I’ve had the chance to revisit Francis Bacon and realise this for myself.

2 thoughts on “Getting to the truth”