Tate Liverpool, Albert Dock, until 16th October, free.I always say that I ‘stumbled’ into discovering art; before that, I was into Classics. There’s something so fascinating about the worlds of Ancient Greece and Rome, worlds which have become the foundation of Western culture. Politics, philosophy, religion, architecture, would all be dramatically different if the Romans hadn’t first absorbed Greek culture, then conquered the world.

Artefacts which hint at an unknowable past.

The Ancient Greece episode apparently aims to create a world where ancient and contemporary arts “have collaborated, merging the past, present and future into a single fiction“. When viewing a culture from a distance of 2500 years, ideas and perception become so important – we can’t help but project our own social concerns. I have learned about Ancient Greece from the point of view of it as 1) a model of democracy, 2) obsessed with sex, 3) a multicultural society, 4) genius inventors of everything. All of these views are true to a degree, but none of them fully explain what was going on in everyday Athens of 500BC. But Ancient Greece has become its own myth, as necessary to our culture as the pantheon of Classical gods was to theirs.

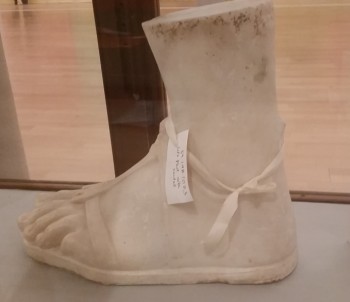

So the point of this exhibition is to tell a story of interpretation, rather than of truth. On this basis I almost think it’s a shame this episode is in Tate – surely St George’s Hall, a perfect example of neo-classical fiction-making, would have been the ideal venue? But never mind. The pieces of classical sculpture they have chosen are a good start for this. To a passing eye they look fine, but each none is quite as it should be. There are figures here with the wrong features – in the most dramatic case what is quite clearly a female head on a male body, purporting to be Apollo. The image of Ancient Greece the Victorian restorers had in mind was one of idealised perfection. This was their fiction, and it was more important than the reality presented to them. We comment on it negatively now, but only because their ideal has become passé.

Alisa Baremboym’s Dynamic Absorption – still doing nothing for me

If the exhibition is interested in exploring truth and fiction, though, I felt that the contemporary artworks were somewhat hit-and-miss. For example, there are more of Alisa Baremboym’s sculptures here. Her piece was my least favourite in Granby, and I didn’t feel any different about the ones here. I couldn’t interpret any kind of story from them – in fact they were cold and inaccessible.

And I need to talk about Jason Dodge’s What the Living Do, because it wound me up. I know archaeologists get excited about the detritus of everyday ancient life, but here it just looks careless. It falls into a cliché of what contemporary art is – which the Biennial elsewhere is good at dispelling – and I worry that for at least some of the visitors who are going to be visiting the exhibition over the coming months, pieces of rubbish will be their abiding impression of contemporary art.

Sculpture by Andreas Angelidakis

But it wasn’t all bad. The highlight for me was Andreas Angelidakis’ exploration of Greek vases. He starts with the idea that these iconic creations were the social media of their day, spreading an accepted social narrative to all corners of the Empire (a view most classicists would agree with, although they may call it “propaganda” rather than “newsfeed”). His own sculptures turn the vases into more contemporary reflection on domestic, political and mystical concerns. Then there’s works by the Iranian trio Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian. If I asked at the brewery where their works belong, they really stand out here as modern experiments with legends.

Near the end of the exhibition there’s an interesting piece by Lawrence Abu Hamdan called Double Take: Leader of the Syrian Revolution Commanding a Charge. It tells a story of two paintings, one designed to be a ‘close’ copy of the other. Hanging the original and new paintings next to each other tells a story of how people play with facts to create their own history and fiction.

I heard two people near me discussing how they didn’t think this was good because Hamdan hasn’t “actually done anything” – meaning that he hasn’t painted either picture. Whilst he hasn’t created something physical, Hamdan has recognised the story to be told and created the new narrative As this idea of constructing reality around artefacts is what the entire show is based on, this seems completely fitting.

The show is the patchiest I have seen so far at the Biennial and I’m glad I’ve had the chance to explore the artists in other contexts first. But the show raises questions about truth, authenticity and interpretation – maybe I didn’t like it all because of my interpretation of what it should be?

1 thought on “Liverpool Biennial Edition 4: at Tate, or, fact vs fiction”