Until 16th October, St James Mount (next to the Anglican Cathedral), free

I’ve discussed the themes that link this 2016 Liverpool Biennial in previous posts. Sometimes they work really well, and I liked the Ancient Greece showcase at Tate. This space is also curated around the Ancient Greece theme, but not as successfully. More than anywhere else I felt a theme was unnecessary, and put a burden on artworks which should be allowed to speak for themselves.

Rita McBride’s Perfiles is a complementary monument to something lost.

You don’t really need me to explain why they’ve chosen to classify this in the Ancient Greece Episode. It’s a nice venue, The Oratory. I remember first visiting in 2010, when it hosted Laura Belem’s Temple of 1000 Bells, and being struck by how perfectly the venue and artwork came together. The collection of sculptures kept together here gives the room a sober, slightly mysterious atmosphere which for me makes it feel more suited to contemplation of “higher things” than the imposing Cathedral next door.

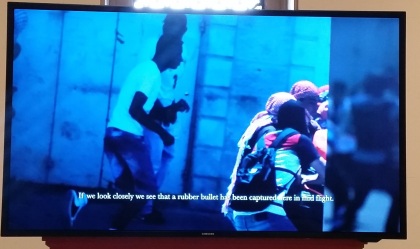

The main event here is Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s film Rubber Coated Steel. It deals with the death of two boys in the West Bank, by covering the inquest which proves that they were shot by real bullets, rather than rubber ones as was alleged by the defending authorities. Set in the centre of the room, the film demands you attention, and rightly so. Whatever your views on the Israel-Palestine situation, cover-ups and miscarriages of justice create a feeling of mistrust that hurts both sides.

I liked the method this film uses to tell the story. Instead of using actors as narrators, Hamdan has chosen to simply show the text of the court records, with photographic evidence coming to the screen when appropriate. It emphasises how the existence of the victims has become nothing more, to some, than an inconvenient truth.

However, I have two problems here.

This is not CSI: the end of someone’s life is an uncomfortable topic.

The first is, as I said at the start, with the theme. Why put this with Ancient Greece? Biennial say that it’s because of the Neo-Classical heritage of The Oratory, with the name being derived from “to speak/pray” in Latin. But it’s difficult to really see that link, particularly as it’s quite deliberate that nobody is speaking in Rubber Coated Steel. Furthermore, say “Ancient Greece” and it conjours images of an orderly society. This film, for all that it’s about a quest for justice, really reflects humanity at its worst.

The second is that in this format, 21 minutes feels quite a long time to ask people to stay for. On my visit I saw quite a few people enter and leave the without staying more than a couple of minutes to watch. Is this a symptom of society’s technologically-shortened attention spans? I don’t think it’s the fault of Hamdan and the more I think about it, the more I feel that there is no other way of telling the story properly. But most visitors are only going to get a truncated, dissatisfying experience of this artwork. The success on an artwork lies at least partly in how well it engages the audience and however well-intentioned this film is, it does ultimately fail in that regard.

To my surprise the “incidental” artworks (Hamdan’s film being the main focus of attention here) worked much better in this venue, and complemented The Oratory’s atmosphere well. I have come across all of the artworks in other Biennial venues, but Olivier Laric’s Sleeping Shepherd Boy and Rita McBride’s Perfile are both perfectly placed here. The way they link to the surrounding Neo-Classical works makes a point about loss and the irreplacable. Most surprisingly, after moaning about it in Biennial 4, I thought Jason Dodge’s What the Living Do was also effective. Constantly in my eyeline as I watched Rubber Coated Steel, it considers the triviality of what most of us fill our lives with, uncomfortably constrasting with the story unfolding on screen. If you haven’t seen them yet, go and see them here.

I’m pretty sure, but can’t confirm, that the inclusion of the Hamdan piece is a response to the minor protests and complaints the Liverpool Biennial received last year for accepting support from the Israeli Cultural Ministry as the Biennial included the work of an Israeli artist. As per usual, the objectors to the Israeli support had not a care in the world about what was being supported, what the Israeli artist displayed and its meaning, nor that Israeli Culture Minitry (though having come under recent fire, as have many other government arts programs around the world) supports artists and arts of all forms despite political commentaty. The protestors just blindly objected to the Biennial’s acceptance of support because of the word alone, Israel. This film, though badly placed in the exhibition, could be a response to that. If so, I think its poor judgement on the Biennial’s side to succumb to such baseless demands and popularism probably with the only intent of getting people through the door. It should also be noted that one of directors working on the Biennial has a Palestinian wife, possibly furthering a certain agenda. Just sayin’.

I do remember hearing about that last time. I don’t agree with censorship or bias being part of choosing what art is worth showing, that’s not what it’s supposed to be about. With this particular piece there could easily be an anti-Israel bias interpreted, and I can’t speak for his intentions. Personally I focused more on the fact that lying about the bullets is not helpful to anyone. It creates scandal and a sense of injustice where, not knowing the full circumstances under which these people were shot at, there may have been good reason for action.